Project Outline

The sharia debate and the Shaping of Muslim and Christian Identities in Northern Nigeria

Priority area “How do we Perceive or Shape “Foreign” and “Native” Cultural Identities”

Religions play a major role in the process of identity shaping both at the global and at the local level. The world religions Islam and Christianity offer international contacts to their adherents and at the same time help to identify the borders between the “foreign” and the “own” and sometimes also the “native” identity. Often they are perceived as more or less monolithic in themselves – especially when there are conflicts between Christians and Muslims. At the same time, however, the adaptation of the religious codes to a situation can often lead to the shaping of a particular outlook of either Islam or Christianity.

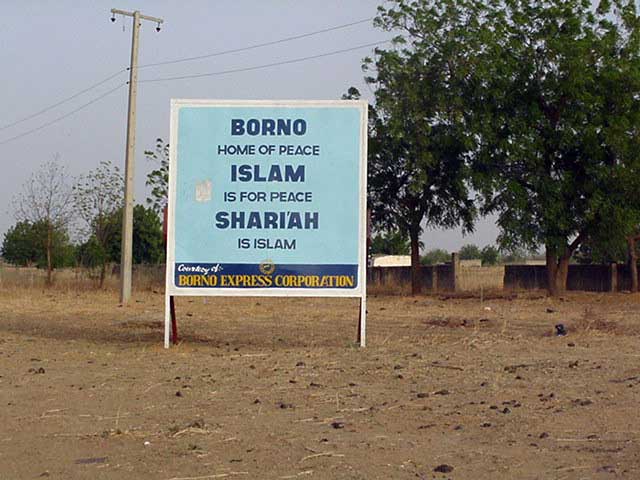

The proposed research project analyses the process of the shaping of religious identities in the context of the sharia debate in Northern Nigeria. Since Nigeria as the state with the largest population in sub-Saharan Africa accommodates more Muslims[1] and more Christians than any other African state, the debate is not confined to its boundaries but of much wider significance. Since Nigeria has regained international credit by its successful transition to democracy in 1999[2], the various steps taken to implement sharia in twelve Northern states of Nigeria[3] are also watched with anxiety.[4] As the most significant and the most controversial changes in Nigeria’s laws in many years they have given rise to a very great deal of discussion - in the popular press, at conferences, and to a limited extent in the academic literature.

The proposed research project analyses the process of the shaping of religious identities in the context of the sharia debate in Northern Nigeria. Since Nigeria as the state with the largest population in sub-Saharan Africa accommodates more Muslims[1] and more Christians than any other African state, the debate is not confined to its boundaries but of much wider significance. Since Nigeria has regained international credit by its successful transition to democracy in 1999[2], the various steps taken to implement sharia in twelve Northern states of Nigeria[3] are also watched with anxiety.[4] As the most significant and the most controversial changes in Nigeria’s laws in many years they have given rise to a very great deal of discussion - in the popular press, at conferences, and to a limited extent in the academic literature.

However, there has not yet been a detached academic analysis of the steps taken to implement sharia and its impact on the shaping of identities. Since protagonists of the parties concerned tend to present their views in the light of a more or less monolithic tradition and to emphasise the complete harmony with the world-wide tenets of their respective religions, there has been a tendency to generalise and to perceive the situation as a conflict between two clearly defined antagonistic camps. There are numerous accounts which describe the events in terms of „orientalism“ – of „islamisation“ and „jihad“ against Christianity and/or democracy and/or secularism. Most Western observers are in solidarity with Northern Nigerian Christians which are seen as suppressed by Muslims. On the other hand, many Muslims also tend to analyse the situation in Northern Nigeria in the line of a tradition of suppression (or of the suppression of a tradition). In an interpretation which may be termed “occidentalist” they see the introduction of sharia as the restitution of their rights which have been taken during the colonial period.[5] “Orientalist” and “occidentalist” tendencies have been revived and become stronger since the debate has been overshadowed by the riots in Kaduna in February 2000 and in Jos in September 2001 as well as by the September 11 attacks in New York.[6] However (as may be expected to be stated in a research proposal) the situation is more complex.

It is the aim of the project to show that also in situations of crises the religious identities are not as static as it may seem, but that a constant and pluriform process is in progress, in which these identities are reshaped. As will be shown, Nigerian Muslims (1) and Nigerian Christians (2) appeal both to global traditions of their faith and are interacting with the world-wide Muslim or Christian communities. At the same time, they are constantly redefining their positions and adapting them in different ways to different local conditions. This process of change and innovation also affects the interreligious relations (3).

It is the aim of the project to show that also in situations of crises the religious identities are not as static as it may seem, but that a constant and pluriform process is in progress, in which these identities are reshaped. As will be shown, Nigerian Muslims (1) and Nigerian Christians (2) appeal both to global traditions of their faith and are interacting with the world-wide Muslim or Christian communities. At the same time, they are constantly redefining their positions and adapting them in different ways to different local conditions. This process of change and innovation also affects the interreligious relations (3).

It is new and innovative to look at the shaping of identities through the sharia debate in an interreligious context and to analyse seemingly paradox developments: Muslims as well as Christians are “invoking traditions” in order to justify their views, but also something new and specific to Nigeria is developing. The speakers of the respective groups stress uniformity, but at the same time the situation is becoming more pluralistic. While the researches are not striving towards a final judgement on sharia which would tend to foster polarisation and would make it at least extremely difficult for Christian, Muslim and agnostic scholars to work together in a research team – as individuals they hold different views –, they are united in their goal to analyse and to clarify the global and the local dimensions of these processes.

Applicants: Dr. Umar Danfulani (Department of Religious Studies, Jos University, Nigeria); Assoc.-Prof. Dr. Jamila Nasir, Dr. Philip Ostien (both Faculty of Law, Jos University, Nigeria);

Prof. Dr. Ulrich Berner (Religious Studies, Bayreuth University, Germany), PD Dr. Dr. Frieder Ludwig (Ev.-Theol. Fakultät, Munich University, Germany)

Project Co-ordinator: Dr. Franz Kogelmann (Islamic Studies, University of Bayreuth, Germany)

[1] Cf. A.A. Mazrui, ”From Uthman Dan Fodio to Bill Gates”, in: Weekly Trust, August 18-24.2000: “There are more Muslims in Nigeria than in any Arab country. The presence of Islam in this country is becoming a major exceptional factor on the African continent.” To the Muslim scholar Mazrui, the discussion of sharia is therefore a unique experiment to seriously debate an alternative to the Western constitutional and legal option.

[2] Cf. Auswärtiges Amt, ”Die bilateralen Beziehungen zwischen Nigeria und Deutschland”. ”Nach dem Übergang zur Zivilregierung und dem Amtsantritt von Präsident Obasanjo im Mai 1999 konnten die bilateralen Beziehungen wieder deutlich intensiviert werden. Präsident Obasanjo genießt in Deutschland großes Vertrauen (...)”

[3] Zamfara, Sokoto, Katsina, Kano, Jigawa, Yobe, Borno, Bauchi, Kaduna, Niger, Kebbi and Gombe.

[4] Cf. For instance the reports by amnesty international: htpp://www.2.amnesty.de

[5] Up till 1960 was Northern Nigeria the only place outside the Arabian peninsula in which the Islamic law was applied in criminal litigation –with some few limitations. When they first gained control of the North after 1900, the British had banned certain Islamic punishments – cutting off of limbs, stoning, crucifixion – as being “repugnant to natural justice, equity and good conscience “. Cf. N. Anderson, Law Reform in the Muslim World, 1976, 27-28

[6] Cf. ”Stunde der Eiferer”, in: Der Spiegel, 12. November 2001: ”Am Tag der Terrorattacke auf die USA griff Olusegun Obasanjo zum Telephon. Der Präsident rief am 11. September jene Gouverneure an, bei denen ”etwas passieren könnte”. Denn in weiten Teilen vergiften Spannungen das Verhältnis zwischen Christen und Muslimen, seit ein Drittel der 36 Bundesstaaten offiziell die Scharia eingeführt hat. (...) Am 12. September gingen Christen und Muslime in der Stadt Jos mit Macheten und Benzinbomben aufeinander los – über 500 Menschen starben.” – As will be elaborated later, the riots in Jos (which started on 7 September) were not exclusively determined by religious factors. Another example is Frank Räther, ”Der Ruf nach einem Moslem-Staat wird lauter. Im Norden Nigerias eskaliert die Gewalt. Bin Laden wird zur Leitfigur der Separatisten”, Berliner Zeitung, 16. 10. 2001. For a more diffentiating view see Y.S. Muhammed, Hero Worship” , in: BBC Focus on Africa, 51: “(...) Zamfara`s politicians then went on a charm offensive to convince the wider world that the jubilant scenes were an aberration. The state governors sent a letter of condolence to the United States (...).”